Breton mode: embroidery reserved for subscribers

A la mode bretonne series: 3/8

While Breton peasants have for centuries possessed a work coat and another for ceremony or celebration, the latter remains cut from the same fabric, based on linen and hemp. Before the French Revolution, in fact, the third estate was forbidden - if it ever had the means - to use more precious fabrics such as lace or silk, which were then reserved for the clergy and the nobility.

In 1792, the Convention repealed these laws called sumptuaries, and everyone could now dress with the materials they wanted and that they could buy. “There were no typical costumes in Brittany before the French Revolution of 1789, mainly as a result of the restrictions, explain Geneviève Jouanic and Viviane Hélias, in a book devoted to embroidery in Lower Brittany (*). It was at this time that the different regional costumes appeared, influenced by Parisian fashions. »

The development of traditional costumes

Rapidly, the many countries that make up Brittany will adorn themselves with costumes, in order to mark their differences and their identity. These clothes constitute a kind of uniform, very codified, which indicates the geographical origin of the wearer, his profession but also his social condition. "The paranoid obsession with republican uniformity responded to a reflex obsession with singularity", specifies Erwan Vallerie in his book "These Bretons are crazy".

How to Compose Your Center of Interest: Composition makes photography both challenging and fun. By following t... http://t.co/ht8TyIQGpf

— Phil Beale Sat May 18 18:04:10 +0000 2013

"It was in the 19th century that Breton costume became more diverse: each town, each village, each district of town made it a point of honor to distinguish itself from the neighbor through the interplay of embroidery and colors..." Thus, the Quimpérois dressed in shades of blue, while the inhabitants of the country of Elliant wore predominantly yellow costumes. The shape of the pants, the dress, the chupenn (the famous waistcoat) can vary. There were more than 65 models throughout the Armorican peninsula at the end of the 19th century.

A sign of wealth

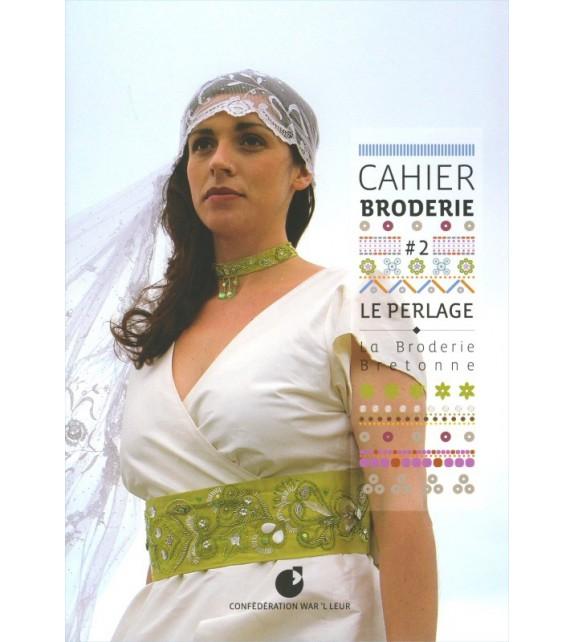

While in the early 1800s these festive garments were still made with the traditional fabrics, woven by peasant families themselves, the industrial revolution and the appearance mechanical looms in France and then the gradual development of the railway made it possible to import into Brittany more affordable and different fabrics (such as velvet) produced in Lyonnais or the North of France, but also decorative materials such as silk or gold thread, as well as pearls. From the second half of the 19th century, Breton costumes were adorned with embroidery, all the more luxurious the richer the owner of the costume. Generally, such a garment is made for a special occasion, such as a communion or a wedding, then it is kept for other events such as important religious holidays that mark the calendar.

The birth of a profession

Across Brittany, traditional costumes have evolved over the years and feature embroidery, often of Parisian inspiration, specify Geneviève Jouanic and Viviane Hélias, using floral motifs adapted for women's dresses or aprons and chupennoù men. They are made by embroiderers with a shop in town that employs workers, the latter reproducing models seen in catalogs. But it is thanks to the embroiderers based in the countryside, particularly in Cornwall, that “the regional patterns will see the light of day.

Sometimes drawing inspiration (from city embroiderers), the peasant embroiderer creates his own designs, influenced by his land; this is how fashions (Bigouden, Glazic, Melenig) gave birth to this embroidery which flourished in the south of Lower Brittany”. The most famous are those of the Bigouden country, which stand out for the finesse of their work and the diversity of the patterns. We generally find on their works the heart (symbol of love), the sun (joy), the chain of life (advocating trust in God), the ram's horn (strength) or even the fern (fertility).

At the start of the 20th century, Breton embroideries were even exported to Paris, with many Bigouden families working for the major Parisian houses.

To find out more

“Traditional fashions and costumes of Brittany” by René-Yves Creston, Kendalc’h editions, 1999.

( *) “Embroidery in Lower Brittany” by Geneviève Jouanic and Viviane Hélias, Jos editions, 1996.

Our selection of articles to understand the dossier A la mode bretonne: behind appearances, a story

The First World War marked the end of the golden age of Breton embroidery. After the armistice, traditional costumes became darker and more sober, and their use became rare with the rural exodus. In fact, these peasant embroiderers are gradually disappearing. Between the wars, Marie-Anne Le Minor founded her company in Pont-l'Abbé and decided to gather around her the embroiderers of the Bigouden country, in order to perpetuate this invaluable know-how, which is now part of the Breton cultural heritage. The Minor declines these embroideries not only on traditional clothing, but also on table and household linen, dolls' clothes and liturgical accessories.

In the 1990s, the Breton designer Pascal Jaouen seized on this cultural element for his collections, bringing Breton embroidery up to date in fashion: "I was born in Bannalec in 1962 and I had the chance during my childhood to meet women who wore the traditional costume every day. When I joined the Celtic circle, I became aware of this superb heritage that was in danger of disappearing. I became very attached to these fashions of dress which, in my opinion, had to be safeguarded”. Pascal Jaouen therefore created his company in Quimper in 1995 to perpetuate this tradition. Today, the School of Art Embroidery trains more than 1,000 people a year and its haute-embroidery workshop develops collections, in order to show that Breton embroidery can also be contemporary...