François Dubet: "The confinement test reveals inequalities that can become hatred"

La Tribune - This very special moment at the start of confinement, how do you experience it intimately, how do you interpret it intellectually?

François Dubet - Although my situation is relatively "comfortable" - I am not alone, we have a garden and we do not miss reading - confinement is a test. We are far from those we love, and we don't know when we will see them again.

Observing the world through the screens, I have the feeling of being totally dependent on the always distressing flow of information. The rare outings in the streets, where we hear especially the birds, are also "freaking". But it is above all the relationship to time that is painful, since we cannot project ourselves onto any date; it is therefore necessary to furnish this time with a succession of small rites so that it is not diluted in an indistinct duration. Let's not hide that this ordeal will be more and more difficult to bear and that we will probably come out of it a little different and tired.

Intellectually, I have the feeling of being deeply destabilized, because the problems which occupied me, like the writing of a book with Marie Duru-Bellat on the paradoxes of school massification, become a little ridiculous. I read a book published three weeks ago on the Democratic primaries in the United States, and already it seems to be dated as its issues are beyond our concerns.

We are not at war - a clumsy formula - but it is like a war: everything becomes urgent, essential, vital, and no one really anticipates the end. Not only do questions of survival arise, but we know that tomorrow, things will not return to their normal course and that our debates will no longer be the same: impoverishment, debt, disruption of trade, explosion of unemployment...

We feel the kind of "panic" that seizes us, including among those whose job is to think and do science: many become epidemiologists overnight. And as always when we don't really know what is happening and what needs to be done, the weirdest and most conspiratorial theories take precedence since nothing is worse than not explaining to us what is happening.

Any explanation rather than emptiness, and rather intentions to harm rather than chains of causes... In this situation, I try to trust those who know and those who act, because I don't I have no other reasonable choice. Also I try not to be connected all day in order to keep a minimum of reason.

Containment dramatically highlights inequalities. Those, for example, linked to the place and the material conditions of confinement, the image of Parisians on the beaches of Cap Ferret colliding with the invisibility of those curled up in their HLM in Seine-Saint-Denis. Those also of access to protective equipment, digital mastery ("illectronism"), etc. You are worried about the possibility that confinement will increase the perception of "small inequalities", those commonly neglected but which the anger of the yellow vests had highlighted, those which exacerbate bitterness and resentment, those which ultimately fragment, compartmentalize, fracture the more society. Those that could provoke violence, either visible or internalized. In what forms can these "silent" inequalities break out? What "other" inequalities does this ordeal of confinement reveal(s)?

Rightly, the social sciences, many think tanks and economists in the wake of Thomas Piketty, have highlighted the growth of inequalities over the past thirty years. The inequalities that they measure and denounce are in fact the very great inequalities, those which oppose the 5%, 1%, 0.1%, even the 0.0.1% to the rest of the population. They are right insofar as wealth accumulates on a minority of the population, which poses economic problems, social and fiscal problems and not only problems of justice, since a part of societies thus escapes life. "ordinary" society and state control.

However, this perspective has led to ignoring the "small inequalities", those perceived by individuals in their daily lives, at work, at school, in the city. In France, these inequalities have not exploded and in some areas, they have even been reduced. But for individuals, they are unbearable for several reasons. The first is a transformation of the "inequality regime". Indeed, as long as we lived in an industrial, class society, inequalities were relatively congruent and engendered a collective experience. They opposed “us”, “us” the workers, “us” the “bourgeois”, “us” the peasants... We compared each other from group to group. For about thirty years, this system of inequalities has come undone, and the latter have multiplied more than they have exploded. It is the individuals more than the collectives who experience themselves as unequal because each crystallizes in themselves several dimensions of inequalities: I am unequal "as a" woman, peri-urban, poorly educated, divorced, distant from my work, " as "young, old, connected or not...

Consequently, inequalities are experienced as forms of discrimination and manifestations of contempt that are all the more unbearable in that the feeling of the fundamental equality of all has not ceased to grow stronger, in accordance with the grand narrative of the democratic "providence" of Toqueville. For example, over the past thirty years, inequalities between women and men have "objectively" been reduced, but those that remain are much more unbearable.

Another example, until the 1970s, the great educational inequalities opposed young people who had access to higher education to those who worked; however, today, all or almost all study, but they do not follow the same studies, they are sorted within the school system itself, and the feeling of injustice in the face of these "small inequalities" in school is much more acute than when only a minority studied.

The virality of conspiratorial theses on the origin of the virus is the megaphone: the anarchy of the ways in which the perception of these inequalities is expressed, opens the way to a democratic and political disorder with unsuspected consequences...

The movement of the yellow vests is an illustration of this: it protested less against the "bosses" and Bernard Arnault than it opposed the "small inequalities" which rot life and, even more, the feeling of being despised. , to be invisible and ignored. But, at the same time, this movement did not produce any collective demand, each carrying its own anger. We can hypothesize that covid-19 will exacerbate this experience of inequalities since, as you say, everyone compares themselves as closely as possible: house or apartment, ability or impossibility to help children's school work, connection effective or isolation... The test of confinement reveals inequalities that could be considered insignificant or self-evident. As with the yellow vests, these inequalities have no collective and political expression, so they can become hatreds, beliefs in conspiracies, populist imaginations... In a worst-case scenario, we can always imagine that inequalities are multiplying: why this region more than that, why masks here and not there...? While the "old" class inequalities had a political expression, multiple inequalities are experienced as personal hardships deprived of collective expression, they are individualized and multiplied without aggregating...

... Evidenced by the controversy in the United States - revealing the vicissitudes of the federal organization - suspecting the White House of favoring the supply of sanitary equipment in States, such as Florida, favorable to the electoral strategy of Donald Trump. The pandemic mainly kills the elderly or already frail. The intergenerational bias is both a glaring marker of inequalities and a keystone of "making society". Consideration for the elderly, the role and the place conferred on them, could they evolve tomorrow?

Every year, the flu kills the elderly far more than the young. I suppose there may be natural fragilities. With the heat wave of 2003, we discovered that EHPADs and retirement homes protected less than we thought. The elderly died much more in France than in Spain and Italy where they stayed more with their children, for lack of an effective welfare state. And then, we forgot this episode... to rediscover it today.

What is most shocking is the scarcity of means of resuscitation which would require sorting the sick according to their hope of recovery when, a priori, all lives are equal. We had never imagined finding ourselves in the situation of practicing war medicine.

We also discover to what extent our lives depend on the welfare state and public services: the work of the couple requires a school system, various aids and support for school holidays. The elderly are a matter of the State more than of families. While France is rather well armed in terms of social protection, it is not excluded that the pandemic will lead us tomorrow to heartbreaking revisions in favor of local and family solidarity, arrangements for working hours. Perhaps all that is called "care work", care, will have to be redefined, distributed in another way also within families on the one hand, and between families and communities on the other. .

Solidarity: the pandemic indeed questions in a burning way what makes it up, what, in us and in society, irrigates and extinguishes it, and the cause of the elders is a perhaps salutary crystallization...

Obviously, I do not want a return to domestic solidarity supported by women alone, but the division of labor within families and between families and the State today reveals its fragility in French society which, I repeat, is not the least protective and the least redistributive. In the same way that a model of economic development will no longer be tenable, a model of the welfare state and solidarity will no longer be. We will have to ask the community to help us to show solidarity, rather than entrusting, by delegation, solidarity to the State alone.

Conversely, it is undeniable that the pandemic breaks certain dikes consubstantial with inequalities: it strikes independently of heritage, status, social class, financial means, territories, countries, continents... The perception of can this erasure make a lasting impression, that is to say, thanks to this "equal vulnerability", help to realize that tomorrow "we" will have to work to fight against "unjust inequalities"?

For all we know, the Covid-19 is blind and democratic. It hits everyone and forces everyone to protect themselves while protecting others. At the same time as it reveals inequalities in living conditions, it is a factor of solidarity since everyone's survival depends on others, including those who were hardly visible and valued. From this point of view, as in the aftermath of wars, many inequalities will be perceived as unbearable. After the war of 14-18, we wondered why society divided "those whom the trenches had united". But this is the optimistic scenario because one can imagine, on the contrary, that fear leads to war of all against all.

In any case, the universality of risk and the imperative of solidarity will force us to question the justice of inequalities. Is it fair that a nurse's aide, a truck driver, a cashier or a delivery man be doomed to low wages and precariousness when we now know that their work is so vital? On the other hand, is it fair that very high incomes are totally disconnected from the “social utility” of the work accomplished? He who earns a hundred times more than another is never a hundred times more indispensable. One can imagine that these questions, hitherto somewhat abstract, are all the more necessary as we will have to face an economic crisis such that it will be necessary to share the sacrifices, the losses, and not the profits.

With regard to any inequality, it is necessary to distinguish between perception and reality. The extent, today incalculable, unimaginable, of the economic and therefore social and even humanitarian repercussions of this crisis, could profoundly modify the "subject itself" of inequalities, both in its dimensions of perception and of reality. How "democracy" - more exactly each lever of democracy: the executive, the legislature, the intermediary bodies, the spaces of direct or participative democracy - should it, perhaps from now on, take hold of the subject?

The perception of social inequalities does not reflect real inequalities. Each society adheres more or less to a philosophy of social justice which leads it to perceive inequalities or some of them as more or less acceptable. For example, Americans are less scandalized by social inequalities than are Scandinavians, while inequalities are much higher in the United States than in northern Europe; as for liberal societies, convinced of the extent of social mobility, they tolerate inequalities better than social democratic societies. But social mobility is not, in fact, greater in the first societies. Representations count as much, if not more, than facts.

These representations will undoubtedly play a role tomorrow. That said, my concern concerns less representations and imaginations than political capacities. What the post-pandemic future will be will depend on the political capacities of democratic societies.

Either they will be able to organize a debate and take decisions recognized as legitimate, or they will not be able to do so and we can fear the worst: anarchic paralysis which has a good chance of leading to authoritarian regimes or " illiberals". The current political situation may legitimately cause concern: how could the democratic political systems that have been greatly destabilized in recent years could offer courageous and democratic political prospects between fragile majorities, powerful populist movements and "uncontrollable and uncontrolled" demagogues now in power in many "big countries"? As for the future of Europe, there are also good reasons not to be very optimistic - but everyone knows that national responses will not weigh on the state of the world.

Not all inequalities are harmful or unfair, some are driving and stimulating, they contribute to the progress of individuals, to the progress of a "community". Can a redistribution of "good" and "bad" inequalities emerge from this crisis?

If you've never made a water rocket before, sign up to our workshop, learn how to build one and then launch it! http://t.co/F3VE4smd

— NPL Mon Jun 11 15:05:02 +0000 2012

The question of inequalities has never presented itself as an alternative between absolute egalitarianism and the acceptance of all inequalities. Fortunately, we don't have to choose between North Korea - all equal but one - and Hayek - all inequality is good as long as it comes from an open market. All of the surveys conducted on this issue show that individuals are a little more subtle and think that they should be equal in certain areas, such as their fundamental freedoms and the satisfaction of their basic needs. On the other hand, they believe that certain inequalities are acceptable when they sanction effort, merit and contribution to the common good. And the French appear fairly broadly “rawlsian”: they judge that the inequalities resulting from meritocratic competition are acceptable when the worst off see their situation improve. The debate has never opposed equality and inequalities, it is that of acceptable inequalities and to a certain extent useful to all. On this last point, I do not believe in the “trickle down” theory, the fable according to which the hyper-wealth of some is good for the poorest.

You quote the sociologist Emile Durkheim, author of the principle of "organic solidarity": the work of each contributes to collective life, social cohesion results from the interdependence of individuals among themselves. Could the ordeal we are undergoing today later give this principle a new dimension? And already upset some of the referents, benchmarks, mechanisms that orchestrate the collective organization of solidarity, and beforehand that feed our intimate conception and exercise of solidarity?

We must return to the notion of solidarity because the search for equality presupposes that we show solidarity with others, with those we do not know and for whom we are ready to make sacrifices: paying progressive imports or contributing to universal insurance. Solidarity is based on a symbolic dimension: beliefs and common representations attach us to each other, in particular religious beliefs since we would all be "brothers" by being the sons (less often the daughters) of the same god. In modern societies, it is essentially the nation which offers this symbolic dimension of solidarity, and which calls for the "supreme sacrifices".

But there is another account of solidarity, Saint-Simonian, then Durkheimian and solidarist, according to which symbolic ties do not stand up well to modern individualism, to the capitalist division of labor and to religious disenchantment. In this case, society is considered to be an organism, a "hive" to which everyone contributes through their work. The more intense the division of labor, the more we depend on others and the more others depend on us. Only the idlers and the "parasites" benefit from this system without contributing to it. In this case, solidarism, then socialism, consists of a system of rights and protections linked to work which opens up debts and claims: each worker gives to society and the latter must "return" this gift to him. The modern social state and the wage society were built in this way, through social redistribution, we give back to the workers, to the pensioners... what they gave to society. In national industrial societies, this representation of solidarity was extremely powerful because it transformed a class conflict into a set of social rights and duties. It was called social progress.

Social progress of which these springs of solidarity seem to have collapsed over time...

Indeed, this representation has gradually weakened, and we find it difficult, with globalization, the proliferation of exchanges and mobility, to represent society to us in this organic form. If the pandemic has one virtue, and only one, it is to remind us of our dependencies and our debts to those we do not know. We are no longer in a society of pure individuals in competition, a society of winners and losers, but in a whole on which we depend and which depends on us. The reasoning can be extended beyond national societies: we depend on all other humans and even on nature which invites itself to the table of rights... If this vision is not imposed, we risk experiencing a archaic return of only symbolic and identity solidarities: withdrawal into identities, nations, neighbours, withdrawal against all the others. While this virus is that of globalization, the worst solution would be nationalist, identity closures, and ultimately: war, the real one! We must therefore both reunite each society and strengthen international governance. I'm not sure this scenario is favored by Putin, Trump and a few others.

The event, perhaps even civilizational, that we are embarking on will have immense consequences on jobs. It could also generate repercussions, of all kinds, on "the" work - this work one of the main levers from which we shape our identity, we construct ourselves intimately and socially -: our relationship to work, the place we give to work in our existence, the hierarchy of priorities of "values" related to work - tomorrow search for meaning more than money? And in companies, work organizations, management systems, internal power relations...

I never believed in the decline of work and the civilization of work. We have been so obsessed with employment that we have sometimes ended up forgetting that work is a social bond, a solidarity, an identity, and one of the major expressions of human creativity. It is enough to observe the experience of unemployment to see that work is not only an "unfortunate obligation to earn a living". However, without repeating the accepted criticisms of neoliberalism and neo-management, it is clear that we have often degraded working conditions, we have ignored pride, professional identities, we have acted as if wealth were only produced by brilliant managers. We cannot imagine that the desirable return of solidarity does not lead to a rehabilitation of work.

The problem is not new, particularly in France where collective bargaining capacities remain particularly weak, as weak as are the unions which believe they have no other choice than confrontation, faced with leaders who think have no choice but to relax the statutes and make workers more flexible.

Each day delivers its uninterrupted flow of predictions or hopes. The dystopian prophecies confront the scenarios of a revolution in consciousness and behavior, a radical change of paradigm. Your colleague Michel Wieviorka categorizes them as follows: the blasé ("everything will go back to how it was before"), the pessimists ("it will be worse tomorrow") and the optimists, among whom are intertwined to varying degrees candor, faith, fatalism, utopia, determination, hope. The human and social sciences, and particularly sociologists, examine society as it was and as it is. Not as it will be. In this singular moment, what should be the contribution of sociologists, anthropologists, ethologists, philosophers to understand but also, “a little”, to prepare?

No one can anticipate the personal and collective state in which we will be after six weeks of confinement, in France and in most countries. Only certainty, it will not be "like before". A priori it will be worse, since an explosion of unemployment, an increased indebtedness, an exacerbated mistrust towards the persons in charge of any nature, seem assured... It will be worse also because many among us will be traumatized and bereaved. But, if we have the political and intellectual dispositions, we can imagine a renewal of our capacities for action: how to rebuild a globalization that does not weaken all the economies, how to restore solidarity and equality, how to act in nature and not against she ? All these questions which were locked up in the more or less "above ground" criticisms, become essential.

The human and social sciences could play a role in this situation if they developed an ethic of modesty and seriousness by saying what is possible and what the effects of our decisions will be. This remark may sound grumpy and bitter - confinement is not a good adviser (smile). But how can we fail to observe that the taste for the indignant pose, for the denunciation, for the continuous updating of the perversity of domination and power, that the desire to reduce everything to simplistic explanations, occupy the stage and invade the web? Rather than adding to the hysteria of the web and networks, we should take a course of modest "positivism": say what we know, what we have studied, what we learn from story. The intellectual and academic world should ask itself: why are its positions and its choices often so far removed from social life? I have always been very surprised by the intellectual situation in the United States: campuses that are often ultra-critical, radical, engaged in multiple studies... and, on the side, a society that votes for Trump and considers as an admissible opinion that the earth is flat... France is not so different.

It is undeniable that the role of the “real” experts, in the first place of the professionals of the medical sciences, benefits from a substantial revival of recognition. At last ! moreover, the television sets usually polluted by charlatans, show more rigor and vigilance. Can this crisis make it possible to "re-legitimize" science in the eyes of a public opinion which shows so much distrust of it? Can these human and social sciences, which are increasingly "relegated" - even within the academic and political worlds - also be better able to have their usefulness "recognized"?

Not on the web but on the "normal" media, anti-scientific nonsense has receded. It would be hard to claim that vaccines are more dangerous than viruses and that doctors don't know anything about it. The fact of deciding on a policy based on scientific advice does not seem to me to be questionable. Even though we are faced with the greatest uncertainty, we do not really have an alternative to science, to its interrogations and its quarrels which are part of normal scientific life. In this regard, the pandemic is rather welcome. The human sciences, I insist, would do well to offer modest and serious analyzes so as not to fall into the sole world of opinions. They undoubtedly have material to study and say about the social mechanisms revealed by the pandemic since we see that societies do not react and do not act in the same way. The question of their usefulness, often denied in the name of the refusal of utilitarianism, is even more essential today. I have always thought it: since teacher-researchers are financed by taxes and duties paid by all citizens, they owe something to society, they must "account" - which does not mean "accountable" .

The relegation of the human and social sciences within the academic world comes from the very functioning of higher education and research: they do not welcome the best of students because they offer uncertain professional outlets - France is not not the only country in this case. We are, in part, responsible for this situation insofar as the most scholarly and professional productions remain confined to journals essential to scientific exchanges and, even more so, to academic careers, while in the public space, this knowledge disappears and is replaced by opinions and often postures.

Already the prospects of legal retaliation against the State, the rulers, the public authorities accused of shortcomings in the management and especially the anticipation of the crisis, are great. The extent will be proportionate to that of the judicialization and the disempowerment of consciences and actions. This observation raises two questions: hasn't the constitutionalized precautionary principle, within society, seriously poisoned consciences, the exercise of responsibility beyond its original perimeter? Could the scientists, to whom the executive constantly refers to explain and...justify its decisions, become the expiatory victim in the event of a humanitarian disaster?

We have not come out of the pandemic that already, I am already being asked to sign a call for a lawsuit against Emmanuel Macron, Edouard Philippe and a few others, for "endangerment", and even "high treason"... I find this terrifying , because it translates the search for scapegoats: "they" knew, "they" lied, "they" knowingly killed... At the collective level, it is nothing other than the denunciation of his accused nurse neighbor to spread the virus. Obviously, we will have to explain ourselves and explain how we got there, and ask ourselves if we acted as it should. But those who sneered at the stocks of masks accumulated unnecessarily following the flu, today denounce the lack of foresight of the rulers...

The mechanism is always the same: if there are effects - a pandemic - there are causes, and behind the causes stand intentions to harm. "They", the powerful, the scientists, the caste, the Chinese, and why not, the Jews and the Muslims... are behind all this. What was settled by a few pogroms and a few stakes, now has justice as its theater. This is the worst case scenario for the exit from the crisis. Le pire parce que chacun se dédouane de ses propres responsabilités : je dénonce le tourisme de masse, mais je revendique le droit de partir en vacances où bon me semble ; je dénonce la mondialisation mais j'adore les vêtements produits au Bangladesh... Le "système" fonctionne parce que chacun y participe avec enthousiasme, tant qu'il fonctionne. Aussi, ces appels aux procès sont souvent des manières de se défaire de sa propre culpabilité. Les partis qui réclamaient la tenue du premier tour du scrutin municipale, accusent aujourd'hui le gouvernement de les avoir suivis.

Certes, il faudra bien que nous comprenions ce qui est arrivé et pourquoi nous avons agi comme nous l'avons fait. Mais c'est moins le rôle de la justice que celui des institutions démocratiques. Et c'est pourquoi la métaphore de la guerre est dangereuse : le virus n'est pas une armée ennemie et la guerre appelle des traîtres et des héros, ce qui n'est pas le cas de la pandémie qui exigerait plutôt de la responsabilité et de la fermeté de caractère.

Dans et au sortir de la crise, la "responsabilité d'éduquer" est et sera centrale. Pour expliquer, pour aider à comprendre, à discerner, à tirer les enseignements et même à "se construire" autrement. Les parents, particulièrement aujourd'hui, l'école particulièrement demain, sont et seront sur le front. C'est, pour une mère, un père, un enseignant et pour l'Education nationale, une épreuve ; peut-être aussi une opportunité ?

Il n'était pas nécessaire d'attendre la pandémie pour constater que la longue période de massification scolaire est aujourd'hui à bout de souffle. La promesse de justice sociale n'a été tenue que très partiellement et c'est désormais à l'intérieur même du système scolaire que se multiplient les inégalités. La promesse du capital humain, celle de l'accroissement général des compétences n'a été tenue que pour les vainqueurs de la compétition scolaire - les autres sont confrontés à la dévaluation des diplômes et au déclassement. Enfin, la promesse démocratique, selon laquelle l'éducation de masse devait renforcer la confiance démocratique et la confiance tout court, n'est tenue que pour les plus diplômés qui constituent une élite culturelle, politique et sociale contre laquelle se retournent les vaincus de la complétion scolaire. Aujourd'hui, les électorats sont davantage définis par les niveaux de diplôme que par les critères classiques de classe sociale.

Si l'enjeu dominant de la sortie de la pandémie est celui de la solidarité et de la confiance démocratique, je ne vois comment l'école ne pourrait pas être interrogée. Plus que le fonctionnement de l'école, c'est le modèle éducatif français lui-même qui sera bousculé. Evidemment, les parents ne seront pas transformés en enseignants, mais les relations aux apprentissages, au temps de travail, aux évaluations scolaires, ne sortiront pas indemnes de cette crise. On peut cependant être optimiste quand on voit à quel point les enseignants, souvent perçus comme frileux et repliés sur leurs traditions pédagogiques, se mobilisent, inventent, se lient à leurs élèves, ne comptent pas leur temps. Il semble que 10% des élèves soient aujourd'hui à l'écart. C'est beaucoup, mais je n'aurais pas spontanément parié sur un chiffre aussi faible. Peut-être que la pandémie transformera davantage l'école et l'université que n'ont pu le faire les ministres.

Le chef de l'Etat l'a affirmé lors de son allocution du 16 mars annonçant le confinement. "Lorsque nous serons sortis vainqueurs [de la guerre contre le coronavirus], le jour d'après ce ne sera pas un retour aux jours d'avant (...). Cette période nous aura beaucoup appris. Beaucoup de certitudes, de convictions sont balayées, (...). et je saurai aussi avec vous en tirer toutes les conséquences (...). Hissons-nous individuellement et collectivement à la hauteur du moment". En résumé, comment imaginez-vous et comment espérez-vous que prenne forme ce "jour d'après" ?

Ce qui rend la situation si difficile, c'est qu'on peut tout imaginer. Un chose est sûre cependant : nous ne sortirons pas du confinement aussi rapidement que nous y sommes entrés. Il y aura des phases, des étapes, des transitions, des remises en route progressives, et nous allons entrer dans une période politique puisque la politique ne consistera plus à accompagner les changements face à une évolution vécue comme plus ou moins irréversible. Mes espoirs concernent notre capacité politique collective, c'est-à-dire notre capacité de dessiner un avenir et de gérer nos conflits. Mes inquiétudes concernent aussi cette capacité. Quand on est confiné, quand on perd l'expérience directe du monde social, les espoirs et les inquiétudes flottent et changent sans cesse. Et ça, c'est épuisant.

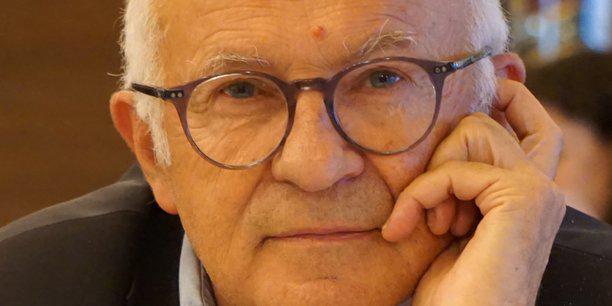

François Dubet est professeur émérite à l'université Bordeaux-II et directeur d'études à l'Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS). Dernier ouvrage paru : Le Temps des passions tristes : Inégalités et populisme, (Coédition Seuil-La République des idées, mars 2019).

Denis Lafay30 mins

Share :