Instagram shops sell clothes from Shein, AliExpress and Amazon

A few months ago, I came across a fashion brand on Instagram claiming to be a woman-owned boutique based in Los Angeles. Her Instagram bio's tagline, "Modification is innovation," suggested that the brand advocated modification of clothing and sold clothing that was recycled or made from old and discarded fabrics.

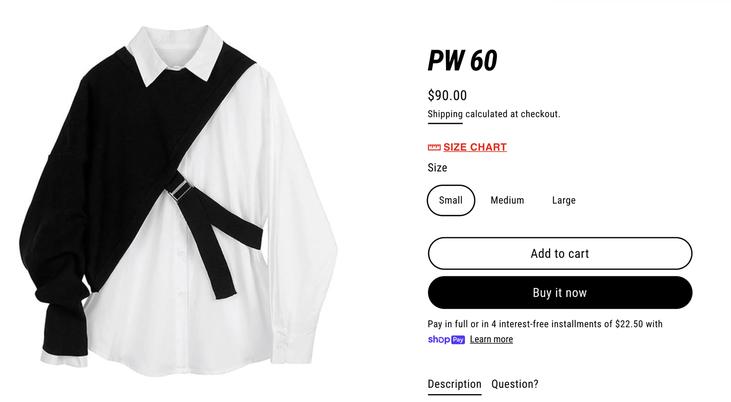

The only red flag was the price of her clothes, which ranged from $60 to $150. These weren't fast fashion prices, but they seemed oddly low for handcrafted clothes. A quick image search The reverse of the brand's products confirmed my doubts.Google results took me to another Instagram store as well as AliExpress, a Chinese marketplace, where the exact pieces (with the same promotional images) were being sold for less half of the listed price.

I was stunned. The original styles and marketing had led me to believe that the brand was producing and designing its own clothes, rather than sourcing pre-made styles from overseas manufacturers. Instead, like the many other “Ghost stores” floating around the Instagram abyss, he appeared to be just another – albeit barely identifiable – cog in the fast fashion machine. (The brand did not respond to requests for comment. )

Instagram spent years tweaking its interface, enticing users to buy on the app. Its transformation into a shopping destination was quick, sudden, and unsurprising. It paved the way for a specific type of online business, or "Insta store" to thrive. These stores don't always sell products exclusively on Instagram; they rely on the app to drive customers to their websites, through influencer marketing or targeted ads. As more and more people turn to social media to find new products and brands, shoppers have also become wary.

People are realizing that some brands aren't exactly what they say they are: independent, ethical stores run by small business owners and designers. In some cases, shoppers find they've paid at least the double the price of an item of clothing found on marketplace sites like YesStyle, Amazon, and AliExpress, or from Chinese fast-fashion retailer Shein. For example, a Business Insider reporter purchased two dresses for around $34 each at It's Juliet , an Instagram store that claims to sell “ethically made” clothing, find the exact same styles on AliExpress for $10 each.

What is of concern to customers is the origins of the merchandise in question. While some brands are clearly buying items from places like Amazon or Shein and reselling them for a profit, others seem to be engaging in a practice where they don't have merchandise on hand at all, called "drop shipping." who make a living from the app.)

These virtual storefronts are what I call “ghost stores”: faceless, indistinguishable businesses with few original products. These merchants rarely disclose the nuances of their business models. safe from consumer blowback Either. That's because the entrepreneurs behind these brands are adept at building a digital facade. They've learned how to earn customer trust through relentless marketing on social media or by crafting a compelling and vague “brand story” that reveals minimal information about founders and workers.

The appeal of these "ghost stores" is based on somewhat ineffable factors. We buy from the brands we do because we connect with certain elements of the business, whether it's superficial factors like clothing designs unique or something more identity and moralizing, like sustainability. When we learn that a company is nothing more than the story it tells – that it exists for purely profitable reasons – it can seem misleading .It is of course in every brand's interest to create a narrative that attracts customers.It could be argued that the entire retail industry relies on some level of deception.

Traditionally, customers also don't care where and how their products are made. After all, many reputable retailers are used to sourcing from the same factories and suppliers, while using white label, or rebranding, of their items to conceal this fact. Yet the illusion of difference and exclusivity is comforting. It cements a sense of loyalty between the customer and the brand. Back when we were doing most from our purchases in physical stores, that claim seemed believable. Now, all it takes is a simple Google search and the facade crumbles.

To be clear, resale and dropshipping are not illegal or inherently harmful practices, although factors such as product quality and authentication are in question. Dropshipping is actually a fulfillment model decades old originally used by sellers of furniture and appliances. Merchants list products for sale without having any inventory on hand. Merchant agrees with manufacturers to buy the products at lower wholesale prices , allowing them to mark up the cost of profit. When an item is sold, the drop shipper coordinates with the supplier to send the goods directly to the customer. This is often a process over which the merchant has no control. check, and items can take weeks or months to arrive.

[before invention of wood-glue] Man (holding up 2 pieces of wood): im very unsure of how to get these 2 pieces of wood to stick together

—Joel Wed Tue 04 23:41:32 +0000 2020

Other ghost stores have limited merchandise on hand and store it in a studio or warehouse. These virtual brands aren't exactly drop shippers, as they have access to inventory. Still, they tend to buy in bulk. from suppliers, like Shein or AliExpress, who work with drop shippers. The Instagram clothing store I met, for example, displays photos and videos of its Los Angeles studio and showroom, and occasionally features workers handling and shipping clothes. This belies the fact that his clothes are largely indistinguishable from those of EAM, an AliExpress store and supplier, and other Instagram shops.

Reproducibility is a telltale sign that these brands source from the same suppliers, even if they feign authenticity and originality. mass production of goods, reveals the reality of these companies. It lays bare what writer Jenny O'Dell has described as "the categorical deception at the heart of all branding and retailing." Consumers are starting to notice and to wonder, for example, why they see the same pants everywhere, just with a different brand label. The purchase starts to look like a scam, even if it's not quite.

Lisa Fevral, a Canadian artist who produces video essays on fashion and culture, has grown suspicious of a particular genre of small Instagram shops, selling trendy clothing styles and aggressively promoting ads In a recent video, Fevral called them "doppelganger brands." They have names like Cider, Kollyy, Omighty, Emmiol, and Juicici and, in his view, appeared to be selling clothes from the same Chinese suppliers. (Fevral was originally approached by a Cider rep to promote the brand, but said she turned down the offer.) What worries Fevral, however, is the effort to green their brands to fool gullible customers. .

"These companies are clearly targeting young women, but it seems like they're trying to adjust their language to sound more sustainable or ethical while not changing much to their practices," Fevral told me. There's no way for a company to follow TikTok's styles and trends unless it produces a lot of super cheap clothes. »

Cider, who Business of Fashion has described as "the next Shein," received $22 million in venture capital investment in June to expand her operations. On Cider's "about us" page, she claims to be a "socially-focused, world-first" brand that reduces waste by operating on a pre-order model and "only [produces] specific styles that we know people want in a controlled amount. Its CEO also told Business of Fashion that Cider places orders for small batches of styles. Still, customers have claimed to find copies of his clothes on AliExpress for slightly lower prices, suggesting that Cider – or his suppliers – may be producing and selling additional garments elsewhere. (Cider did not respond to email or Instagram requests for comment.)

"It's so easy for a brand to add another section in their about page to make you feel better about supporting them," Fevral said. [about its greenwashing practices]. These brands don't care.

It doesn't matter whether sites like Cider are drop shippers or merchants with access to wholesale merchandise. They're not breaking any laws. can be found on other retail sites at comparable prices – is a defining quality of capitalism. What happens if a brand's reputation is damaged? Its architects can simply rename it, start over and continue to source from the same places. A frustrated customer, who bought a leather jacket from a seemingly real German brand, remarked that these "scams are getting so sophisticated" that people should be wary of buying products from digital brands they've never heard of.

That's because there's basically no friction in building a virtual storefront, even though it's essentially a digital facade. A budding retailer only needs a few things: a website, a catchy domain name, an active social media presence and product providers. (Shein is a prime example of this type of direct-to-consumer retailer and has transformed itself into a dropshipping provider.)

Several lesser-known brands with murky roots have emerged from Shein's shadow, offering comparable affordable prices and replicable dress styles. Like Shein and other high-speed fashion retailers, these brands release new styles every week, leaning into fashion “micro-trends” inspired by trendy internet aesthetics, such as dark academia, cottagecore or coco girl. Since the internet has a notoriously short attention span, these trending clothes are not made to last.

In the mission to produce and sell as many clothes as possible, these “ghost shops” are building a fashion monoculture – a monoculture in which consumers buy and wear essentially the same clothes, which are simply sold to them in different boutiques. So , is it even possible to tell these brands apart from more reputable retailers? customer reviews. This requires the consumer to be diligent and vigilant, to do their homework when encountering new brands, especially if they boast questionable origin stories or vague “About Us” pages. Moral of the story? Brands, especially when operating online, are not always what they seem.